The Justice Report is a reader supported publication. Support our work by becoming a paid subscriber or making a one-time donation.

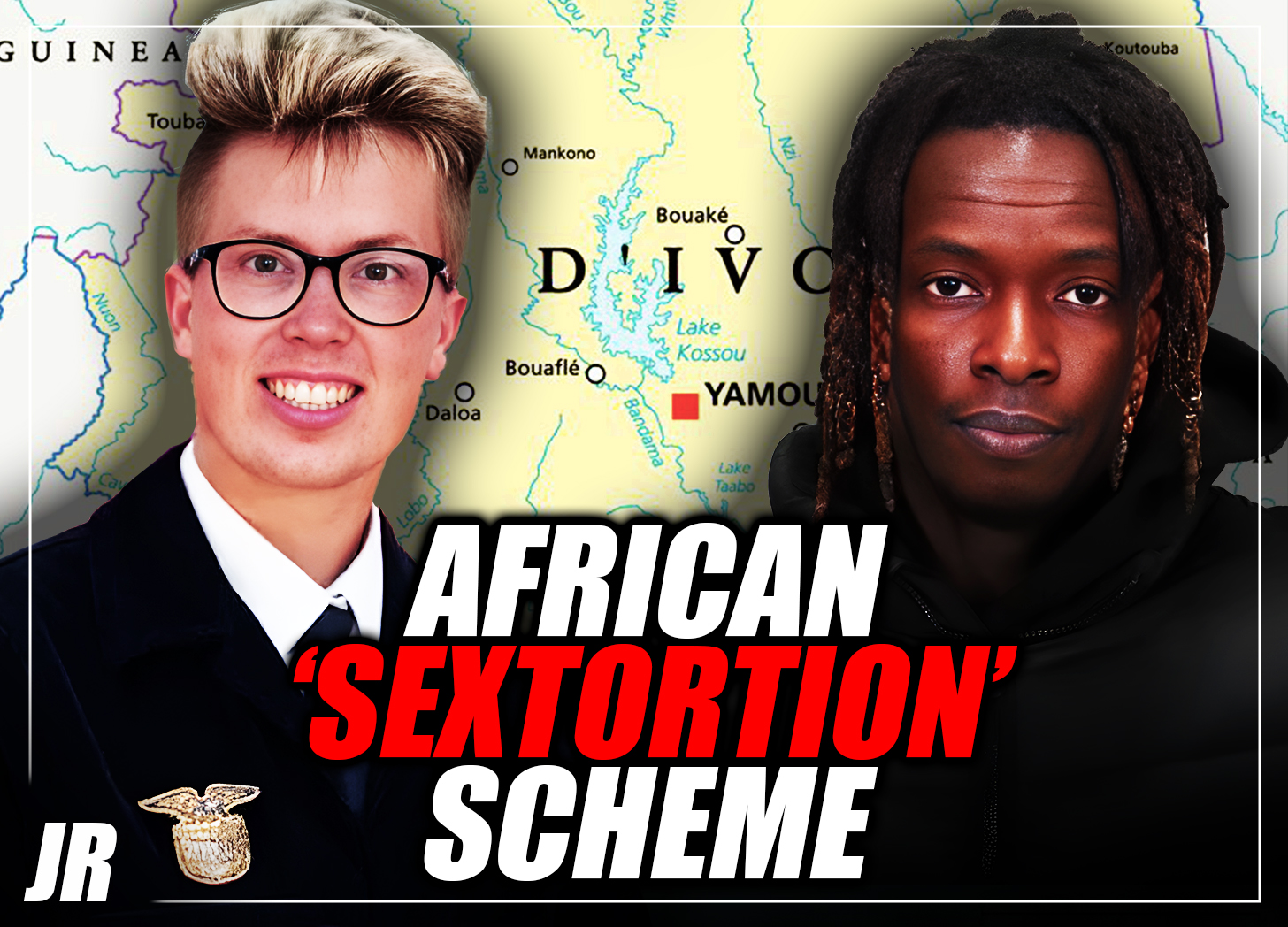

Washington, DC — The U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) and the FBI have deferred prosecution to Ivory Coast (Côte d’Ivoire) authorities after four African men were arrested for a global “sextortion” scheme linked to the suicide of Ryan Last, a 17-year-old White California teen.

Four Ivorian men—Alfred Kassi, Oumarou Ouedraogo, Moussa Diaby, and Oumar Cisse—were arrested for allegedly operating a transnational sextortion ring that victimized thousands, including minors, primarily in Western countries.

Although the FBI led the investigation with assistance from various other American agencies, the Ivory Coast’s policy against extraditing its own citizens means the suspects will face local cybercrime charges instead of prosecution in the United States.

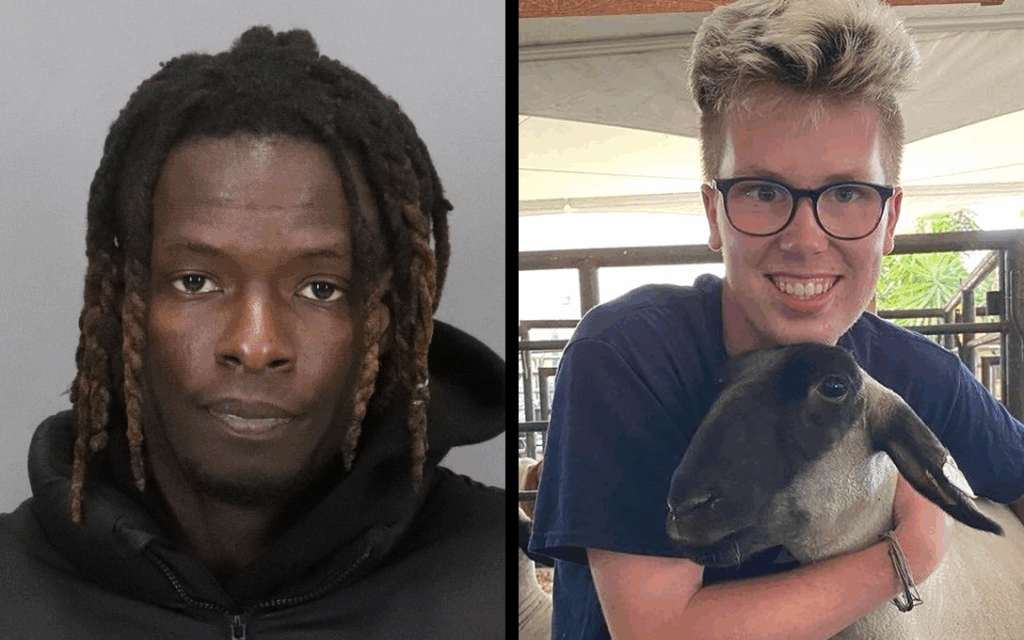

Jonathan Kassi—a Black accomplice to the scheme operating out of the United States—was previously convicted in California for targeting 17-year-old Ryan Last, who died by suicide after being extorted with explicit images. Despite an 18-month sentence, Kassi served fewer than ten months behind bars.

On May 15, Last’s mother, Pauline Stuart spoke with CNN, saying that she was beginning to believe that the remainder of Jonathan Kassi’s accomplices would never face consequences:

“It still seems a little unreal that it happened. I kind of believed that it would never happen, but law enforcement never gave up.”

The Justice Department states that after they showed the Ivorian authorities their evidence, Alfred Kassi was successfully arrested in the African country on April 29. According to reports, Alfred Kassi’s phone still contained the three-year-old extortionist text messages exchanged with Ryan Last.

Four days before the arrest of Alfred Kassi, Ivorian police would arrest Ouedraogo, Diaby and Cisse for laundering the $150 Last had sent them before committing suicide the same night.

Ryan Last was a Straight-A student and a Boy Scout who had visited several colleges he was interested in attending before his suicide.

The scammers originally demanded $5,000 from Last, but eventually took $150 though they continued to harass him for more. Last, who had taken the money from his college savings, wrote in his suicide note that he felt ashamed for risking reputational risk to himself and his family.

Last’s mother, Pauline Stuart recounted to CNN how she had said goodnight to Last at 10 PM and by 2 AM, he had been extorted and had taken his own life. Stuart has remained in the public spotlight ever since, hoping to spread awareness about sextortionists who are willing to target children.

“You need to talk to your kids because we need to make them aware of it,” Pauline Stuart said to CNN.

The FBI has publicly warned that ‘sextortion’ is becoming a fast-growing threat—especially for teenage boys.

According to a recent report, the FBI has received thousands of complaints involving young boys being victimized through schemes similar to the one that targeted Ryan Last.

The report also reveals that since 2021, more than 20 teenage boys who were targeted in these cases have died by suicide. In response, the FBI has intensified its collaboration with international governments—particularly in Africa—to combat the growing crisis.

Sextortion is tracked by the FBI under the broader category of “Extortion/Blackmail” in the Uniform Crime Report. This category includes detailed sub-classifications that capture data on victim-offender relationships, crime locations, weapon involvement, and connections to other criminal offenses.

Strikingly, the data reveals that the typical victim of extortion-related crimes in the United States is a young White male under the age of 30. Approximately 25% of all reported extortion cases involve pornographic material or take place online.

Ivory Coast presents an ideal environment for the proliferation of extortion scams targeting Americans and Europeans.

The population is generally proficient in both English and French, internet access is widespread, and the likelihood of online criminal activity being detected by authorities remains relatively low. Additionally, the West African nation does not extradite its citizens who are accused of crimes in other countries.

The scamming and extortion of White people is also celebrated in Ivorian cultural life. An entire sub-genre of African music has emerged that openly promotes and glorifies fraud, as long as the victims are White and from the West.

Back in 2007, Dominik Kohlhagen, an anthropology and law professor at the University of Paris, shed light on this cultural phenomenon. He explained that the popular Ivorian music style coupé-décalé originated among Ivorian immigrants in France before spreading back to West Africa.

In Paris, young Ivorian scammers would parade luxury goods and piles of cash—often obtained through online fraud—in flashy music videos.

Their message was bold, by tricking White Europeans they claimed they weren’t merely enriching themselves but also “reinvesting in their communities” through every extravagant purchase.

The music soon spread back to Ivory Coast, where it gained cultural momentum. While it draws on broader anti-colonial frustration, the message goes further—it’s not merely about resisting Western systems, but about exploiting them for personal gain.

“If there is a message, what coupé-décalé actually means – well couper in Ivorian slang means to cheat, to cheat somebody, décaler is to run away,” Kohlhagen told Afropop in 2007. “… This message was put forward in quite some provocative way by these young people, saying well we have succeeded here by cheating the whites. … And this is the third word … Couper, décaler, travailler. And travailler means distribute the money, throw the money away, share it with other people on the dance floor.”

The Ivory Coast emerged from a civil war in 2002, the CIA refers to the current political situation in the Ivory Coast as rife with “rampant corruption and inadequate supervision,” which in turn “leave the banking system vulnerable to money laundering.”

Although the United Nations-recognized International Telecommunication Union (ITU) reported a fourfold increase in internet access in Ivory Coast since 2014, only 40% of the population had online connectivity as of last year. Despite this relatively low rate, the FBI has identified Ivory Coast, alongside Nigeria and the Philippines, as one of the primary hubs for online “sextortion” schemes.

Though the FBI observed that scams like the one that took the life of Ryan Last are becoming more common, one thing holding back their exponential growth may be the Ivory Coast’s lack of infrastructure.

According to the CIA, “the lack of a developed financial system limits the country’s utility as a major money-laundering center.”

While the volume of scams may be limited by somewhat primitive Ivorian banking, punishment for extortion scams by Ivorian authorities appears to vary in severity and may depend on who the accused chooses to target.

In 2016, two Ivorian men were convicted in Ivorian court of manslaughter, fraud, blackmail and harassment after the 2015 suicide of their ‘sextortion’ target. Unable to pay the thousands of dollars the Africans demanded, 18-year-old Yanick Paré of Quebec would take his own life after writing a note detailing his secret shame.

The older of the two, then-20-year-old Zeotaba Alain was given five years while his accomplice, then-19-year-old Zida Issouf was sentenced in a juvenile court.

Also in 2016, Ivorian courts would convict a popular-lifestyle influencer known as ‘Commissaire 5500’ of participating in a multi-million-dollar, international ‘sextortion’ scheme. The original sentence does not appear to be in print, however, it is clear that ‘5500’ only served two years behind bars.

While Ivorian courts sentenced ‘Commissaire 5500’ and Zeotaba Alain to significantly longer prison terms than California courts imposed on Jonathan Kassi, those penalties still pale in comparison to the punishment given to one Ivorian man who defrauded his own countrymen.

This March, Joseph Mathias Lebahy was sentenced to ten years in prison for charges relating to a scam he allegedly perpetrated while masquerading as a UN official. Lebahy would have young Ivorians send him money in exchange for opportunities that would advance their socio-economic conditions. Prosecutors had sought a seven-year sentence for Lebahy, but the court handed down an additional three years and imposed millions of dollars in fines.

Consider supporting the Justice Report by donating or becoming a paid subscriber on Substack or our website. Paid subscribers enjoy benefits, including access to audio editions of all our exclusive articles.